The Real Cause of Plantar Fasciitis

The Real Cause of Plantar Fasciitis

By James Speck via Somastruct.

Plantar fasciitis is a poorly understood condition. There is little consensus among medical professionals about the cause of plantar fasciitis, and no treatments have been reliably proven to treat it. A number of theories exist for why plantar fasciitis develops, but the ineffectiveness of conventional treatments suggests something is missing.

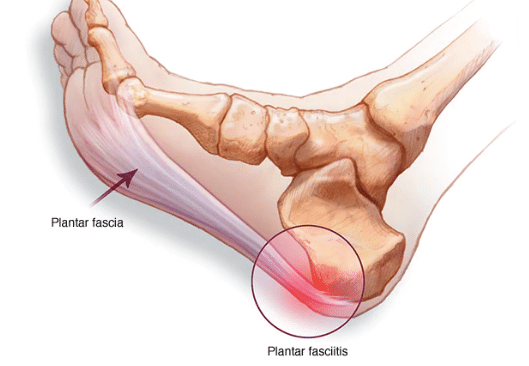

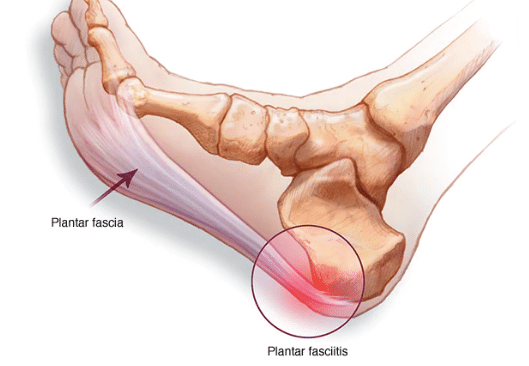

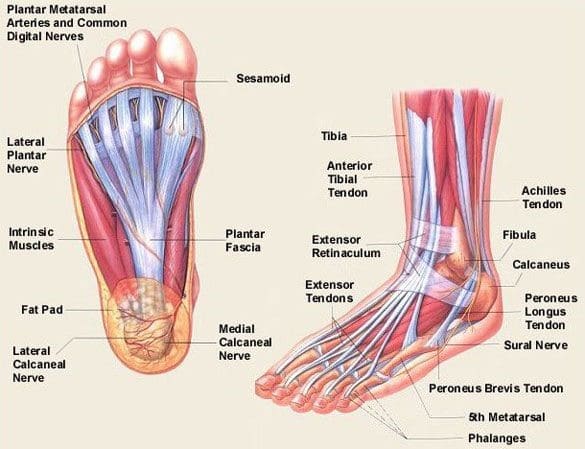

The plantar fascia is a band of connective tissue that runs along the underside of the foot from the heel to the toes. The fascia helps maintain the integrity of the arch, provides shock absorption, and plays an important role in the normal mechanical function of the foot.

Plantar Fasciitis Is Not Inflammation

Plantar fasciitis was previously believed to be inflammation of the fascia near its insertion on the heel bone. The suffix (-itis) means inflammation. Studies, however, reveal that changes in the tissue associated with the injury are degenerative and not related to inflammation, at least not in the way most people typically think of inflammation.

Sudden onset of heel pain may indeed be related to acute inflammation. For persistent heel pain, the condition more closely resembles long-standing degeneration of the plantar fascia near its attachment than inflammation. This could explain why anti-inflammatory medications and injections have been unsuccessful at treating it. But there is more to heel pain than just the plantar fascia.

Not Just Fascia

The pain associated with plantar fasciitis is localised to the underside of the heel towards this inside of the foot. Often overlooked when talking about this injury are the muscles that share an insertion with the plantar fascia. Looking at the muscles in the sole of the foot you can see that the flexor digitorum brevis muscle runs directly above the plantar fascia. On the inside part of the heel the abductor hallucis, an important arch stabilizer muscle, attaches.

It’s not certain that the pain associated with this condition originates in the plantar fascia. Many of the diagnostic features seen with this condition (e.g. bone spurs, thickened fascia) are also found in people without heel pain, and likewise may be absent in people presenting with the injury.

There’s a fair chance the pain is the result of a tendon problem of the muscles deep to the fascia, rather than the fascia itself. The role the foot muscles play in this condition will be discussed later in the article.

Overuse Injury?

The most common theory on how plantar fasciitis develops is that repeated strain on the fascia causes small tears to develop that eventually lead to pain. Excessive pronation (collapse of the arch) is often cited as the cause of increased mechanical loading of the fascia.

Despite how frequently pronation is blamed, there is not much evidence that arch mechanics play a role in the condition. This may be partly due to the difficulty researchers have accurately measuring pronation, especially movement of the arch inside of a shoe. This might also mean though that tensile stress on the fascia from arch movement, at least in itself, is not a cause of plantar fasciitis.

Role of Compression

Animal studies suggest repeated mechanical loading alone may not be enough to cause degeneration of connective tissue. Tissue degeneration is more likely to occur in areas that receive a poor blood supply, or at locations in the connective tissue where the blood supply is cut off.

Another interesting finding is the presence of fibrocartilage near the attachment of the plantar fascia. Fibrocartilage insertions are more common in structures that undergo bending or compressive forces. It may be that bending and compression are a bigger problem than tensile or stretching forces.

Heel spurs were also once thought to be a feature of this condition, with the thinking that they were caused by the fascia pulling away from the bone. New evidence strongly suggests that spurs are unlikely to be a cause of fasciitis, and that they may develop due to compression rather than tensile force on the fascia.

Risk Factors

Currently, no single factor has been reliably identified as contributing to the development of plantar fasciitis.

The two risk factors with the most support from current research:

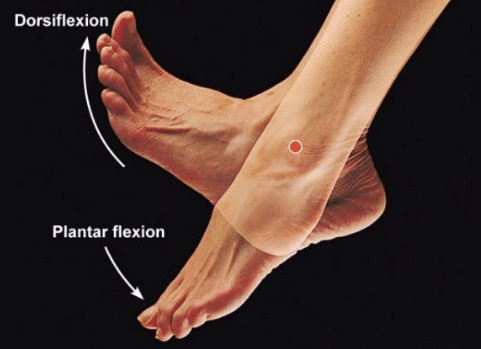

- Decreased ankle dorsiflexion

- Increased Body Mass Index (BMI) in non-athletic populations

These factors are related in that:

- Both lead to increased strain on the arch

- Both lead to increased compression on the heel

When dorsiflexion range of motion (ankle flexibility) is lacking, the body compensates by increasing movement of the arch. In this way, decreased ankle dorsiflexion influences pronation and places strain on the underside of the foot.

Similarly, having a high BMI causes strain because it places a load on the foot that may be in excess of what the foot can support.

As I mentioned earlier, overpronation is thought to be a contributing factor, but studies on this have so far produced mixed results.

The second way these factors relate to each other is in the way people stand. A lack of ankle flexibility and a high BMI can both cause increased pressure on the heel in standing. Keeping weight on the heels causes compression under the heel. But it also means the muscles and ligaments in the arch are not being used to balance your body weight. Lack of use, I suspect, is a greater danger than overuse.

Looking beyond these potential contributors to heel pain though, there is one major factor that overshadows them all–the way footwear alters the normal function of the foot.

A Major Factor: Shoes

There are several features in the design of shoes that can directly cause abnormal stress on the plantar fascia and potentially contribute to disuse of the muscles in the foot.

Toe Spring

I’ve written before about the link between a shoe’s toe spring and plantar fasciitis. Most shoes curve up in the front in the area of the toes. This upward curve of the sole is called a toe spring. This is engineered into footwear because shoes are crudely made compared to the complexity of the structure and function of the foot.

The curve allows for a rocking motion to occur as a person transfers their weight from their heel to the front of their foot. This rocking motion is a substitute for the bending the foot does when walking barefoot–a motion shoes are unable to replicate.

Having this toe spring means that, for the majority of the time when a person is standing or walking in a shoe, their toes are held elevated off the ground. The curvature of the sole places the toes in an extended position. Because of this, the toes can only make contact with the ground when the heel lifts up.

Keeping the toes splinted in this extended position can hypothetically do several things:

- Holds the plantar fascia and other structures in the sole of the foot in an unnaturally elongated position

- Prevents the toes from gripping the ground

- Prevents the intrinsic foot muscles from contracting to support the arch

- Prevents the muscles and plantar fascia from assisting with shock absorption

- Possibly cuts off circulation on the underside of the foot

When walking barefoot the toes make contact with the ground much sooner in the stance phase of gait than they do inside a shoe. These foot muscles are needed to assist with gripping the ground and stabilizing the arch.

Without support from these intrinsic foot muscles, extra strain is placed on the plantar fascia. This extra stress is can be doubly bad because the toe spring also places the plantar fascia in a stretched position. Toe extension (upward movement) stretches the plantar fascia via the windlass mechanism. With the plantar fascia already stretched by the toe spring at the time the foot contacts the ground, its ability to lengthen farther and absorb forces is limited.

Toe spring and a rigid sole are a bad combination. Increased strain on the fascia is not the only problem related to the restricted movement of the toes though. Deep to the plantar fascia are those foot intrinsic muscles with tendon attachments to the heel.

Stress Shielding

Stress-shielding is one theory on how connective tissue injuries happen. Stress-shielding suggests that the part of a tendon exposed to a low amount of strain is where problems develop. This contrasts sharply with the conventional theory that excessive strain is the cause of heel pain.

It’s possible that the restricted movement of the toes leads to degeneration of either the plantar fascia or the tendons of the intrinsic muscles because while wearing a shoe those structures are not put under enough tensile stress! Tissues need movement to remain healthy!

Not only do shoes restrict the ability of the toes to contact the ground, they also limit their ability to fully extend. When going barefoot extension of the big toe is somewhere around 48 degrees. The toe only extends to about 28 degrees when wearing a standard shoe with an orthotic. Because of this, the tissue on the underside of the foot is prevented from moving through a full range of motion. Keeping the foot in such a fixed position for long periods of time during the day could certainly lead problems.

Arch Supports Not Needed

The arch not only supports the weight of the body, it also provides a space underneath the foot for nerves and blood vessels to pass. A structural arch is supported at its ends, not in the middle. Propping the arch of the foot up with an arch support in a shoe doesn’t make sense. The built up arch in a shoe can also alter circulation to the tissue attached to the heel, and it places additional compression force on the underside of the foot.

Inflexible Sole

Similar to the toe spring, a shoe with a rigid sole also alters the natural movements of the foot. Here is a comparison of how a “supportive” running shoe can bend compared to a “barefoot” style shoe.

The supportive shoe has very limited motion, which means it’s going to force the foot to only move a certain way. It has almost no ability to twist, and it bends only at one point along the forefoot. All individuals are built differently. It’s very likely that the few spots where a stability shoe bends aren’t matched perfectly with where your foot can bend and twist. Contrary to traditional thinking, an overly rigid sole is probably worse for the plantar fascia than a flexible one. A rigid sole forces the foot to move not based on anatomy, but in the way the shoe manufacturer thinks a person’s foot should move.

Raised Heel

Most traditional shoes typically are higher in the heel than in the forefoot by at least 10mm. This might not directly affect the plantar fascia, but the raised heel does a couple of undesirable things.

- It places the ankle in a plantar flexed (downward pointed) position which can lead to adaptive shortening of the calf muscles. As noted early, calf inflexibility is suspected as major risk factor for developing plantar fasciitis.

- It alters the way a person distributes their weight on the foot.

- Lastly, the extra cushioning under the heel causes you to strike the ground harder with your heel!

My History With Plantar Heel Pain

About seven years I developed plantar fasciitis in my left foot. A few months earlier I started wearing running shoes and inserts recommended to me by a specialty running store. The “expert” from the store said the shoes and insoles would help with my pronation. I wasn’t running much at the time. My BMI was in the normal range. But I was wearing the shoes for work, standing and walking around in them for eight or nine hours every day.

I tried stretching, ice, taping–all the current recommendations for plantar fasciitis–and none seemed to help. The pain lasted for several months.

What treatment finally worked?

Getting rid of the shoes. A short time after I stopped wearing those particular shoes and insoles the pain went away. Coincidence? Maybe. At the very least that experience convinced me that supportive shoes and orthotics are not a good treatment for plantar fasciitis. If anything, they are the main cause!

Recap The Effects of Footwear

To summarise, modern shoes do several things to the underside of the foot and plantar fascia:

- Limit the natural movement of the foot

- Prevent muscle activity of the muscles that insert on the heel

- Hold the plantar fascia in a stretched position

- Reduce circulation on the underside of the foot

- Cause a heavy heel-striking gait

These effects are more pronounced in stability or motion control shoes, but features like the toe spring are present even in “barefoot” style footwear. Most minimalist shoes on the market have substantial toe springs.

Are shoes enough to cause plantar fasciitis by themselves? Maybe.

But combining a shoe that restricts motion and muscle activity in the foot with increased stress, especially compressive stress, certainly could.

The Takeaway

Plantar fasciitis, or better termed chronic plantar heel pain, is likely caused by a combination of:

- Heel Compression: from standing with weight distributed on the heels

- Abnormal stress on the foot: from decreased ankle flexibility, pronation, or a high BMI

- Footwear: particularly a rigid sole and toe spring, which interferes with foot muscle activity, restricts circulation, and hinders the plantar fascia’s ability to absorb forces

Contrary to popular belief, the condition is not caused by inflammation in the traditional sense, and supportive footwear is possibly more likely to contribute to the problem than help it.

Plantar fasciitis doesn’t develop from overuse or too much stress on plantar fascia. It happens when the wrong kind of stress replaces the good kind of stress that the foot needs to remain healthy. The aim of treatment, therefore, should not be reducing stress on the arch. Instead, treatment should focus on changing the types of stresses being applied and encouraging normal function of the foot. Talk to one of our exercise physiologists for more details and options.

This is Part 1 in a three-part series on Plantar Fasciitis.

- Part 1: The Real Cause of Plantar Fasciitis

- Part 2: Why Common Treatments Don’t Work

- Part 3: Treatment Guide for Plantar Fasciitis

Continue on to Part 2 to learn what studies say about the most commonly used treatments, or skip ahead to Part 3 to learn how to treat the condition.

.

Learn More About Treating Plantar Fasciitis

If you need physio for foot ligament damage, get in touch with us to discuss what options are available. Our physiotherapy Brisbane team offers safe and effective treatment for a range of conditions, call 07 3352 5116 or book an appointment online for more information.

.

Sources:

Wearing SC, Smeathers JE, Urry SR, Hennig EM, Hills AP. The pathomechanics of plantar fasciitis. Sports Med. 2006;36(7):585-611.

McPoil TG, Martin RL, Cornwall MW, Wukich DK, Irrgang JJ, Godges JJ. Heel pain–plantar fasciitis: clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of function, disability, and health from the orthopaedic section of the American Physical Therapy Association. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2008 Apr;38(4):A1-A18.

Orchard J. Plantar fasciitis. BMJ. 2012 Oct 10;345:e6603.

Updated 21/08/2022