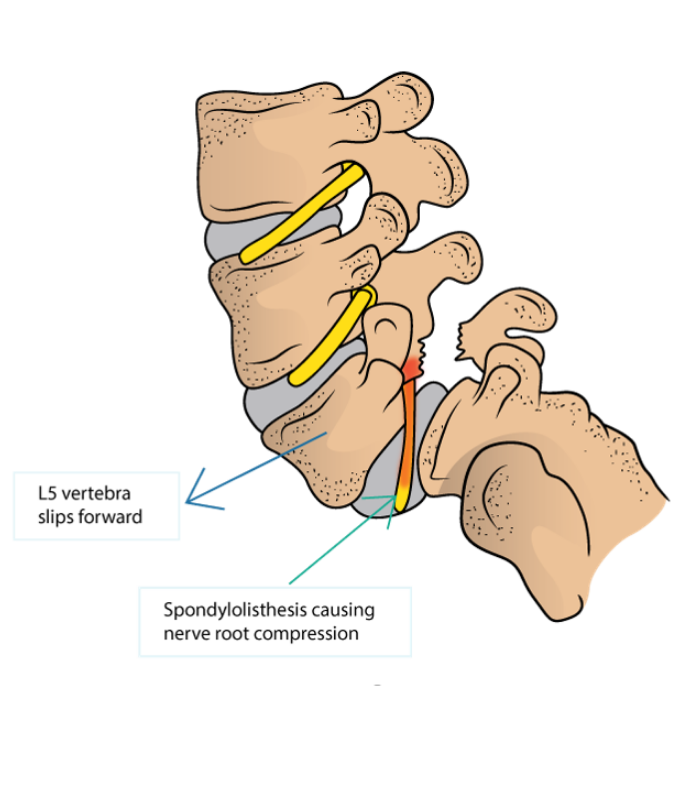

Spondylolisthesis is a condition in which one vertebra slips forward over the vertebrae below it. The slip usually occurs anteriorly at the levels of L5/S1 and causes the vertebra to move out of alignment with the other spinal vertebrae.

This often occurs as a result of a bilateral spondylolysis (stress fracture of the pars interarticularis of the vertebrae), with it being reported that 50-81% of these cases developing a spondylolisthesis. However, this may also occur as a result of birth defects, trauma, or degeneration.

Spondylolisthesis is seen across different age populations. It is one of the causes of lower back pain and leg pain in younger adults under 30, especially in young athletes subjected to repetitive fast pace hyperextension and rotation forces across the lumbar spine. These athletes include gymnasts, cricket bowlers and volleyball players.

On the other end of the spectrum, degenerative spondylolisthesis is a fairly common cause of pain in older adults (age 50 and up).

Traumatic spondylolisthesis can also occur as a result of a significant injury such as motor vehicle accident, being tackled or a fall.

WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS OF SPONDYLOLISTHESIS?

Spondylolisthesis mimics the symptoms of mechanical and radicular lower back pain. Patients often have pain with lumbar extension (bending backwards) which is usually relieved with lumbar flexion. In severe cases a person may assume a hunched forward posture to relieve the pain.

Sometimes there is a feeling of instability in the lower back that is quickly followed by increased muscle tightness and loss of range of motion. In advanced cases where the nerve root is being impacted by the slippage of the vertebra, one may experience pain in the associated segment of the leg or foot innervated by that nerve root.

HOW IS SPONDYLOLISTHESIS PAIN CAUSED?

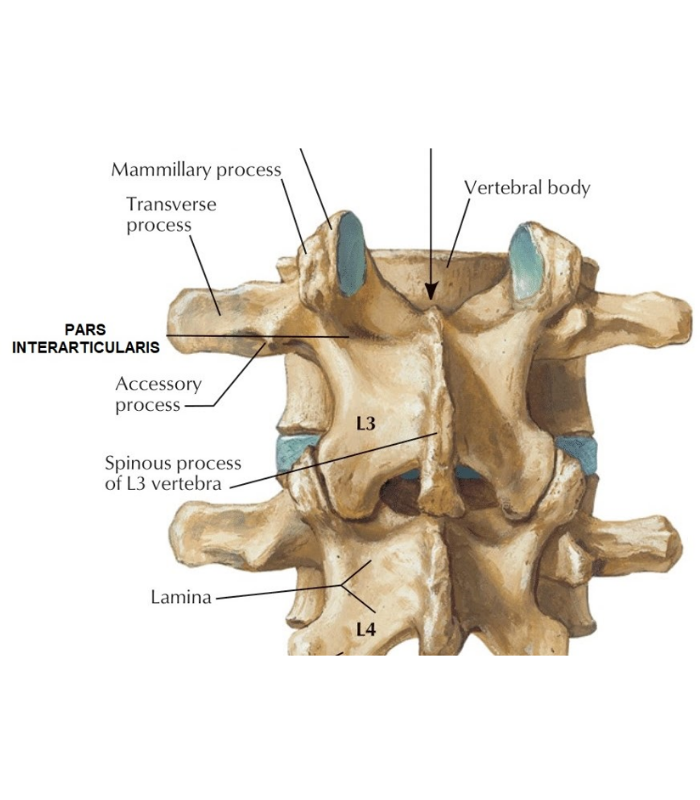

The bones of the spine (vertebrae) connect to each other with several small joints (facet joints). Each vertebra has 2 facets on the upper end, and another 2 facets that sit on the end of the bony processes (pars interarticularis) that extend down towards next vertebra below.

In cases where there are repetitive and large amounts of extension forces going through the spine, especially in combination with rotational forces, the narrow bony bridge (pars) between the vertebral body and the facet joint can sustain a fracture (spondylolysis) or degeneration leading to the disruption of the bony connection between 2 adjacent vertebras. Due to the natural angle of the lumbar curve in this region the affected vertebra will slip forward putting a strain on the facet joints, disc, ligaments, and the nerve roots. In severe cases where both sides of the pars interarticularis are disrupted, structural instability of the spine results.

Spondylolisthesis affects different age groups, ranging from young children and teenagers to the elderly. Some sports that involve fast pace repetitive hyperextension and rotation movements, such as gymnastics, Volleyball, and weightlifting can overload the back bones to the point of causing stress fractures in vertebrae, which can eventually result in spondylolisthesis. Some types of spondylolisthesis are congenital, often manifesting later in life.

Older adults can develop spondylolisthesis because of the occupational wear and tear or normal degenerative changes on the spine. Osteoporosis is a major risk factor in developing compression fractures that lead to pars defects.

HOW CAN PHYSIOTHERAPY HELP?

In acute stages the main focus of physiotherapy is to help manage pain and inflammation, load management and education regarding positioning and activities modification, as well as finding tolerable movement options to reduce deconditioning and strength loss.

For most athletes, temporary cessation of training may be required before a gentle commencement of strengthening. However, after the initial rest period, it is critical that the athlete builds up their abdominal strength, increase their lumbopelvic perception whilst progressively incorporate greater lumbar extension movements.

Long-term physiotherapy treatment includes:

- Anti-extension exercises to improve abdominal strength to counter the lumbar extensors action e.g.:

- Deadbug variations

- Kneeling Swiss ball roll outs

- Planks with time variation

- Improving isometric and isotonic strength of the muscles of the back, hips and trunk that provide stabilisation to the spinal column. Core stability exercises are usually completed with mild to moderate resistance and often performed in closed kinetic chain in neutral position, and then progressively working through larger range of motion to develop core strength in different ranges.

- Postural and movement re-education to promote optimal spine loading and reduce the amount of slippage.

- Stretching and strengthening exercises to decrease the extension forces on the lumbar spine, due to agonist muscle tightness, antagonist weakness, or both, which may result in decreased lumbar lordosis. Stretching distal muscle groups such as hamstrings and lats is also beneficial to allow good mobility and range of body motion.

- Balance and coordination exercises to solidify the newly gained stabilisation skills during complex functional, occupational, or sport-specific movements.

- Cardiovascular and endurance exercise to reduce general levels of inflammation and pain sensitisation

Depending on the stage, different treatment modalities can be used, with manual therapy, exercise and taping and bracing being the most common. Severe spondylolisthesis with impingement of the nerve tissue is often treated with hydrotherapy exercises in the water.

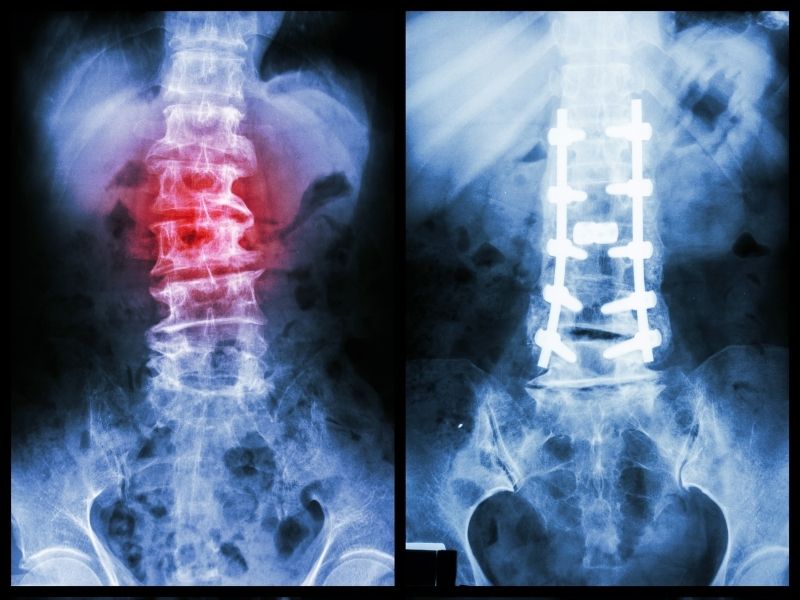

Physiotherapy is usually the first point of call for spondylolisthesis management with best results achieved when care is coordinated between the GP, physiotherapist, and exercise physiologist. In case of poor response to physiotherapy and first-line pain management in the 6-12 months, the patients are subsequently referred for more invasive treatment such as cortisone injections, nerve blocks and surgical interventions that include a varying combination of decompression, fusion and fixation of the affected segment.