Being primary weight bearing joints, hip pain can be at times uncomfortable and require hip physiotherapy.

Prolonged sitting, standing or moving effects our hips. To remain mobile and free of pain, correct loading of the hips is essential and will aid in the longevity of our physical condition. The hips support our upper body weight and are constantly loaded through lower limb kinetics, making hip pain common for individuals with all types of activity levels, and requiring hip physiotherapy.

One of only two ball-and-socket joints in the body, the hips are a unique and essential part of the body’s movement. In charge of posture and keeping our legs going, healthy and strong hips are essential for any lifestyle. However, due to the constant pressure and use, the hips are one of the first major joints to deteriorate. Combined with playing sports that require quick, lateral movements, hip injuries can be commonplace.

PRIMARY FUNCTION OF THE HIP JOINT

The main function of the hips is to enable movement of the legs, essentially enabling us to walk, run and jump. Anatomically, the hip connects major muscle groups such as the quads, glutes and abdominals, making it the key piece in all lower body movements. The hips are also essential for posture, as it takes the weight of the body both when we are standing, and when we are sitting.

ANATOMY, INJURIES & SYMPTOMS OF THE HIP

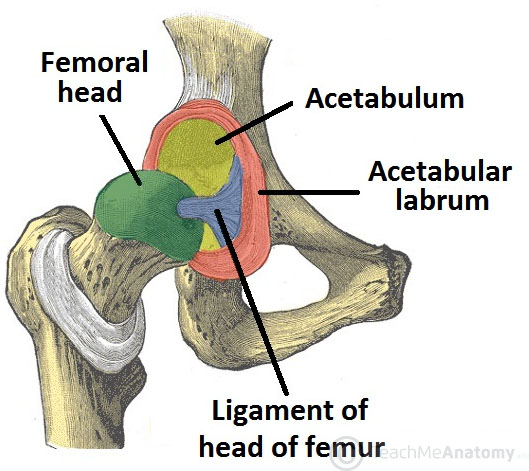

The hip joint is the largest ball and socket joint in the body and is made up of the femoral head (ball) at the top of the femur or thigh bone and acetabulum (socket) which is part of the pelvis. It is surrounded by ligaments, muscles, and a joint capsule. These structures work together to maintain the dynamic stability and provide structural support to the joint.

Being such a pivotal point of movement, it is no surprise that the hips can often feel tight or sore. As the hips are central for many activities, they can often be a key stress point, usually because of body misalignments or contact injuries.

Strains in the groin and hamstring can often be the result of a misaligned or overextended hip joint, as can pain felt lower down the leg. This misalignment or overextension can be the result of contact sports, or the body not properly absorbing the impact felt from running.

Due to the number of muscles associated with the hip, injuries are often a result of multiple factors. Sore or tight muscles, restricted leg movements or swelling and bruising around the joint are all symptoms of a hip injury and can benefit from hip pain physiotherapy.

FEMOROACETABULAR IMPINGEMENT (FAI)

FAI describes an impingement between the femoral head (ball) and acetabulum (socket) within the hip joint. It is seen in approximately 20% of the population and can be caused by multiple changes in the structures around the hip.

PINCER

A Pincer impingement occurs when there is a bony change to the acetabulum. A bone spur develops and extends from the acetabular surface. This injury makes up approximately 42% of all FAI incidences.

This can decrease the range of motion as there is less space between the neck of the femur and acetabulum, this “pinches” the soft tissue surrounding the joint. Hip physiotherapy may be required.

CAM LESION

A Cam Lesion is more common and occurs in 78% of all incidences of people with FAI. A Cam Lesion is an additional growth of bone at the head-neck junction of the femur. This additional portion of bone doesn’t allow the ball to move smoothly with the joint.

A Cam and Pincer impingement of the hip do not always occur in isolation and the most common finding is that both are present. A combination of Pincer and Cam impingement at the hip is seen in 88% of all people found to have FAI.

Those suffering with FAI often present with stiffness and pain in the hip. The issue is felt deep in the joint and is felt at the end range of motion. Pain isn’t always specific to the hip and can present in the groin and lower back.

The most common position of impingement is with hip flexion, internal rotation and adduction. This is due to most cam and pincer lesions being located on the anterior or superior aspect of the hip. The above movement works to bring these two surfaces together.

Those with FAI often have trouble flexing their hip, bringing their knee to their chest.

It has been shown that untreated FAI can lead to earlier onset arthritis so early interventional hip physiotherapy is recommended. With the joint working poorly, there is increased wear and tear to articular cartilage and soft tissue surrounding the joint. Hip pysiotherapy can help to protect the integrity of the joint, whilst teaching fundamental stabilising and motor control exercises which aim to keep normal function at the hip.

LABRAL TEARS

The acetabular labrum is a ring of fibrocartilage connective tissue which attaches to the bony rim of the acetabular. The labrum works to deepen the socket of the hip providing more support for the joint. It helps distribute the forces through the joint over a larger surface area.

FAI has been shown to increase the risk of a labral tear as the impingement increases the force onto the outer margins of the joint. Labral tears are classified into two types. Type I acetabular labral tears involve the detachment of the labrum from the articular surface of the socket. Type II are described as more traditional tears to the labral tissue.

The common signs and symptoms of labral tears are feeling of clicking, catching, locking and occasionally giving way. The pain is often localised to the front of the hip and/or groin, but, can be present in the posterior aspect of the hip. Labral tears are often missed during an x-ray, with MRA being the most reliable method of diagnosis.

Hip pain physiotherapy works to unload the damaged tissue and begin focusing on better neuromuscular control around the hip joint. This increased neuromuscular awareness then provides the addition control around the hip to return to full function. Increasing the control and awareness around the hip also aids in unloading the damaged labrum to allow for healing to occur.

CHONDROPATHY

Chondropathy refers to the disease of the cartilage within the joint. Changes to the cartilage are often seen in association with other hip conditions (FAI, labral tears). Ultimately the damage to the articular cartilage will increase the risk of developing osteoarthritis in the hip.

Osteoarthritis is a degenerative condition where the joint space is reduced due to the breakdown of the articular cartilage. This leads to pain, stiffness and swelling as the joint is unable to move without constant irritation. In severe cases patients undergo joint replacement surgery to maintain functional independence.

HIP FLEXOR INJURIES

The main hip flexor in the body is the iliopsoas, a muscle which runs from our lower back and pelvis and insert on the proximal femur. Hip flexors are responsible for moving our thigh upwards (i.e. our knee to our chest) and are especially important for running and kicking movements. As with all muscles, hip flexor strains are graded; with Grade I being a small tear causing mild pain but no loss of function and a Grade 3 being a complete rupture.

A hip flexor tear most often occurs due to a sudden contraction of the hip flexor at a magnitude greater than it can resist. The most common examples of these are explosive acceleration or in a long kick. Strain or tear can also happen due to repetitive stain or overuse. The symptoms of a strain will depend on how it is graded. As stated above, a Grade I strain will present with mild pain without limit to function, whereas a Grade 2 will be symptomatic with moderate pain and some loss of function. A Grade 3 tear, a full rupture of the hip flexor, will present with severe pain, loss of function, swelling and inflammation, bruising and deformation of the upper thigh.

For all hip flexor injuries physiotherapy treatment and hip injury rehab are required to ensure full and correct recovery. If a strain or tear is suspected, come in and see our team and we can help start your physio for hip pain, or to refer you to the correct health professionals so you can get back to activity as soon as possible.

ILIOSPOAS BURSITIS

A bursa is a fluid filled pouch which assists with movement by decreasing the friction between a bone and overlying soft tissue. Bursas are commonly found at the junction where tendons insert into bone. Bursitis therefore is the inflammation of the bursa which often occurs due to repetitive strain or overuse. Also known as iliopectineal bursa, the iliopsoas bursa is the largest in the body and bursitis for this structure specifically is often caused by repetitive movement of the muscle’s tendon over the bursa, as in running or swimming, rheumatoid arthritis or direct trauma.

Tight hip flexor muscles can contribute to the development of iliopsoas bursitis. An inflamed iliopsoas tendon can also cause bursitis due to the closeness of the two structures.

Iliopsoas bursitis will present with pain and tenderness at the front of the hip, which may radiate through the leg, knee or back. There will also be pain during resisted flexion, passive hyperextension and during internal rotation. A snapping feeling in the hip and increased pain when performing activities may also occur. Hip pain physiotherapy may be beneficial.

INGUINAL HERNIAS

A hernia occurs when an aspect of our internal anatomy protrudes from its normal body cavity, presenting as an abnormal lump, bump or bulge. Usually made up of a portion of the intestine or fatty tissue, these contents will break through a seam in the abdominal wall and exit the cavity through here. Inguinal hernias make up three quarters of all abdominal hernias and occur around the groin/hip region. Significantly more prevalent in males, inguinal hernias are broken into two different groups; direct and indirect.

DIRECT HERNIA

A direct inguinal hernia is when a portion of the intestine or abdominal fatty tissue protrudes out through a weak point in the abdominal wall. The break will generally occur in the inguinal triangle, superior to the inguinal ligament and may be caused by a degradation or deficiency in the number of abdominal muscle fibres. Direct inguinal hernias will look like a round bulge around the groin area and can be painless and often decrease in size when lying face up.

INDIRECT HERNIA

An indirect inguinal hernia is where the protrusion will extend down into the deep inguinal ring and either remain in the inguinal canal or follow the path the testes take into the scrotum. These hernias can be painful and pain will increase when straining, such as for a lift or hold. They may decrease in size when lying supine but the protrusion will get larger as intrabdominal pressure increases.

Hernias are not usually life-threatening; however, they can become so if the hernia becomes strangulated.

Strangulation involves the blood supply of the protruding structure being cut off by the abdominal wall. As the body part needs oxygen from the blood, a lack of supply will become a medical emergency and it is important to present to an appropriate medical professional (probably the hospital) as soon as possible.

GREATER TROCHANTER PAIN SYNDROME (GTPS)

GTPS is a blanket term that involves multiple pathologies that lead to pain on the later aspect of the hip. The point of pain is the greater trochanter, this is a bony landmark that can easily be palpated on the side of the hip. The greater trochanter has a significant amount of soft tissue surrounding and attaching to it.

The gluteus muscles attach to it and there are two bursae that are present around the greater trochanter. Bursa are fluid filled sacks that absorb compression forces within joints to help prevent injury and pain within the joint.

WHAT IS THE CAUSE OF GTPS PAIN?

Hip pain around the greater trochanter was long thought to be primarily due to an inflammation of the bursa, known as bursitis. Bursitis can cause significant pain around the hip and refer pain down the later thigh. Whilst this can be the case, it has now been investigated and the primary cause of GTPS is a pathology of the hip abductor muscles, specifically gluteus medius. The tendon can become inflamed or torn and this can lead to secondary inflammation of the bursa.

Gluteus medius is a primary stabiliser of the hip and helps align the lower limb, specifically in single limb support activity (e.g running). When it is affected or weak biomechanical changes occur and can lead to other issues in the knee, ankle and foot.

HOW IS GTPS TREATED?

Hip physiotherapy for these conditions revolves around a good analysis and understanding of what is the main cause of pain. Physiotherapists are well equipped to analyse movement and make appropriate adjustments to initially protect the injured tissue. Avoiding aggravating activities initially is needed to reduce the inflammation.

Correcting biomechanical abnormalities through strengthening exercises, muscle stretching and reducing muscle tightness is part of physio for hip pain. Educating the patient on correct movement have been shown to help reduce the pain, as well as, prevent further reoccurrences.

MUSCULAR ISSUES AND IMBALANCES AROUND THE HIP

Muscular imbalances around the hip (gluts, hip flexors and lower back) can increase the risk of a variety of injuries. As a range of muscles attach around the joint of the hip, if there is excessive tightness or serious weakness on one side the position of the joint can be altered, this can cause complications at the hip as well as other areas such as the lower back, knee and ankle.

Examples include gluteus medius weakness which can contribute to lower limb alignment. This misalignment can alter the direction and position of force in the knee leading to significant patella femoral knee pain as well as increasing the risk of an ACL tear.

It is therefore incredibly important to ensure that correct loading of the muscle occurs through exercise and if any issues do occur, to have them reviewed by a physiotherapist to remedy and advise on treatment before a lasting problem arises.

The hip is a relatively stable ball-and-socket joint that allows a considerable range of multi-directional movement. The ‘ball’ is formed by the head of the femur and the ‘socket’ is formed by the acetabulum of the pelvis.

The acetabular socket is strong and deepened even further by the presence of a cartilaginous disc that rims the circumference of the acetabulum.

This disc, the acetabular labrum, is responsible for improving the congruence of the joint, as well as distributing forces through the joint.

The head of the femur which is connected to shaft of the bone by the femoral neck covers 60-70 % of a sphere within the acetabulum. The neck-shaft angle (see below) ranges between 120-130 degrees. In addition to this, the femoral head is rotated anteriorly (forward) between 15 and 20 degrees. This is known as the angle of anteversion. A decreased angle of rotation is known as retroversion.

The individual variations in these angles affect the way the shaft of the bone lies as well as the forces that the surrounding muscles generate. An increased angle of anterversion for instance, can cause in-toeing.

THE LIGAMENTS

The main ligaments of the hip are the ischifemoral, iliofemoral and pubofemoral ligaments. These ligaments form the capsule of the hip joint, offering it stability and resisting various planes of movement. Two other ligaments, the angular ligament and the Ligamentum Teres, also form part of the hip complex.

Whilst these smaller ligaments are less involved in providing stability to the joint, the Ligamentum Teres contains a branch of a blood vessel so plays an important part in providing joint nutrition.

THE MUSCLES

The 22 muscles about the hip can be grouped anatomically or functionally.

HIP ADDUCTION

The muscles that adduct (bring the leg towards the body), are known as the adductor group of muscles and consist of the following : anteriorly; the adductor magnus, longus and brevis, gracilis and pectineus; posteriorly; the obturator internus and externus.

HIP FLEXION

The iliopsoas (made up of the iliacus and psoas major and minor muscles) is the major flexor of the hip joint. Along with the Sartorius, rectus femoris and tensor fascia latae (TFL) muscles, the iliopsoas allows bending at the hip. The Sartorius muscle is also responsible for moving the limb up and outwards (abduction and external rotation).

HIP ABDUCTION

The two muscles that serve to abduct or move the lower limb away from the body are the gluteus medius and minimus. These muscles are located on the outside of the hip and are essential for maintaining pelvic stability. This is by the presence of a ‘Trendelenburg’ gait. This occurs when the gluteus medius muscle is weak on the weight bearing side and hence causes the pelvis to sag on the opposite side.

HIP EXTENSION

The muscles at the back of the hip function to extend, externally rotate (rotate outwards) and adduct (bring towards the body) the hip. The muscle action varies based on the attachments and fibre directions, and several muscles have dual functions. For example, the Gluteus maximus, which is the largest muscle of the group, serves to extend and externally rotate the hip. The piriformis muscle is a much smaller muscle with similar functions. Other muscles at the back of the hip include the gemelli superior and inferior, the obturator internus and externus, and quadratus femoris.

HOW DO THE MUSCLES OF THE HIP PROVIDE PROTECTION?

While the muscles of the hip primarily function to allow movement of the lower limb, they also protect the femur from excess loads by providing counteracting compressive forces to the shaft of the femur. This protective mechanism is especially important in those who are diagnosed with osteoporosis.

INJURY AVOIDANCE & RECOVERY FOR HIP INJURIES

Stretching is the key to an injury avoidance, but is made more so due to the wide range of motion the hips can achieve due to its joint type. This increased range of motion is the main reason the hip can be so susceptible to injury, but if properly stretched and warmed up before physical activity, injuries can be avoided. Similarly, increasing the hips’ flexibility through the likes of yoga can also limit the occurrence of injury, as well as potentially improving body functionality and performance.

HOW CAN A PHYSIOTHERAPIST HELP YOU?

While this article covers the very basic contents of hip musculoskeletal anatomy, there are several neural and vascular structures that can also influence pain patterns in the patient. As a clinician, the first step to forming a diagnosis is the patient history.

The mechanism of injury, areas affected and behaviour of the symptoms are the most useful pieces of information one can gather.

Following this, an objective assessment including an assessment of gait, range of movement and special tests of musculoskeletal structures will usually allow for a hypothesis to be made. In some instances, an assessment of the pelvis or lower back may be necessary.

Finally, to obtain a finalised, accurate diagnosis, radiological imaging may be advised. In less severe cases, such as a minor sprain or muscular tightness, expensive imaging is unnecessary and symptoms will often resolve with gentle therapy and exercise.

As daunting as the task may appear, an experienced and knowledgeable physiotherapist is well-equipped to provide the inquisitive patient with an answer or in very tricky cases, a few possible hypotheses and a referral to the radiologist. From then on, you’ll quickly begin your hip physiotherapy and you’ll be on the road to recovery!